Benefits go beyond practicality to brain transformation, science shows

Bilingual education has been a controversial topic riddled with misconceptions, up until recently. History is permeated with false assumptions that have long been disproven, the most prevalent belief was that learning another language at a young age would stunt brain development. Nowadays, due to the extensive amount of evidence found by scientists, the ideas of the past have not only been contradicted but also outweighed by the newfound benefits bilingualism creates.

Research has shown that when a bilingual person uses one language, the other is active at the same time. This process, referred to as language co-activation, was proven through the study of eye movements. When a bilingual person has been asked to locate a certain object in front of them, their eyes have been found to not only gravitate towards the mentioned object but also the object with a similar sounding name when translated into the other language they know.

Due to language co-activation, not only are both languages activated but are also in competition, whether purposefully or subconsciously. “Sometimes when I can’t remember a word in English I just say it in Spanish,” said Rocio-Grace Palusky, a freshman at Minnehaha Academy.

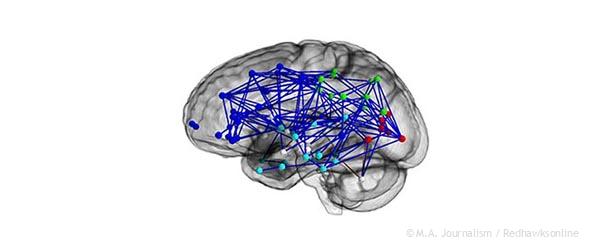

When speaking and listening to others, it becomes necessary for the brain to exercise a system made up of cognitive functions, such as inhibitory control, to preserve the balance between the two warring languages. Inhibitory control is one of the brain’s control mechanisms that give you the ability to ignore competing information and focus on the relevant aspects of the data you are receiving.

“There’s something really awesome about training yourself to listen that carefully,” said Johanna Beck, the Latin teacher at Minnehaha Academy’s Upper School.

The constant use of this function strengthens the brain’s inhibitory control. Tasks that require strong control over the mind’s inhibitory abilities have showcased higher results from bilinguals than monolinguals. One of the most prevalent tasks used to measure this is the Stroop Test or the Color-Word Test. It is a test that dates back as far as the 1930s and has the main target of measuring cognitive functioning. The test measures your capacity to be able to state the color a word is written in and ignore the name of the opposing color the word spells.

A strengthened inhibition not only alters the action of processing information, but also the nervous system’s reaction to auditory input. “It trains you to listen,” said Beck, “[because] you have to pay such close attention, as you’re learning a language, to what’s being communicated.”

Researchers at Northwestern University performed a series of tests monitoring the brain’s reaction to complicated sounds; participants consisted of 23 bilingual and 25 monolingual teens. Both groups were confronted with two separate recordings of speech sounds, one with background noises and one without.

While playing the speech sounds in a quiet environment, both groups reacted similarly. But when the speech sounds with background noises were played, it was observed that the bilingual group members were able to distinguish and concentrate on the relevant sounds and dismiss the irrelevant noises with greater ease and efficiency.

Bilingualism has also been proven to sustain high functioning cognitive systems into old age with greater results than monolinguals. The action of comprehending and conversing in two languages keeps the mind’s cognitive mechanisms active and helps engage alternate pathways in the brain to counteract the damaged networks due to aging, otherwise known as the cognitive reserve theory.

This behavioral concept not only impedes the deterioration of the mind but wards off illnesses that accelerate brain atrophying as well, for instance, Alzheimer’s disease.

In a report from a 2010 volume from the American Academy of Neurology, researchers reported studying more than 200 Alzheimer’s patients, both bilingual and monolingual, it was found that bilingual patients reported starting to see symptoms an average of 5.1 years later and were diagnosed an average of 4.3 years later than monolingual patients.

Researchers also examined brain scans of Alzheimer’s patients in an additional study. They concluded that even when bilingual patients had more physical symptoms present than monolinguals, their behavior remained unaltered despite the results that indicated that they should have had stronger behavioral symptoms.

Not only does being bilingual improve your intellectual abilities, but can also open up doors to different angles of life.

“I think that when you understand and communicate in another language you see things, you understand things, you gain a perspective that you’re never going to get if you’re relying on someone to translate for you,” said Beck.