“Psycho” sets standards for future thriller movies

One of the most recognizable scenes in the history of film occurs in the shower of the first room in Bates Motel. Mary Crane steps behind the curtain, the stress lines on her face relax as the hot water soaks into her skin, and she begins to cleanse her body.

She’s evidently clueless to the shadowed figure wielding a thick kitchen knife stalking her in the bathroom doorway

It doesn’t take long for many to recognize the scene that’s taking place. Even the music alone – rasped violins squeaking a single repeating note, eventually leading to a growing crescendo, and ending in a booming, baritone climax – is enough to spark a familiarity with one of the most praised thrillers of cinema.

One of Alfred Hitchcock’s finest, “Psycho” (1960) was not only a step forward in how terror can impact the screen, but it became the forefather that multiple slasher films would later on try to copy.

Directing more than 60 films in his career, Alfred Hitchcock was and still is one of the most prominent figures in the history of cinema. He has lived to become one of the main influences for several present-day film directors, as well as creating a distinct style that set the standards for various thriller movies to arrive afterward.

A woman determined to marry her boyfriend (who’s unable to divorce his wife due to his inability to meet the correct amount of money), Marry Crane (Janet Leigh) runs away from her home in Phoenix, Arizona with the $40,000 she was trusted to bank earlier that day.

Her hope is that the money will help secure her lover’s divorce. On her way over to tell her boyfriend the good news, she stops for a rest at a barely-noticeable motel on the side of the rode in the thought that she will make the rest of the trip in the morning.

As she makes her way to check in, she meets the motel’s owner, Norman Bates, whose humble voice and taxidermy hobby give signs of a man who may be peculiar, but certainly not dangerous.

Tired from her long journey, Mary resigns to her room, but decides to take a quick shower before she falls asleep. And so begins the psychological roller coaster that broadened the way a movie can represent fear.

Although it was seen as a step forward in how explicit a film can be when first released in theaters, “Psycho’s” charm doesn’t come from its ability to shock the audience with multiple frames filled with blood and gore, but instead it derives from its subtlety.

Partnered with Bernard Herrmann’s famous score, which listening to alone without the visual film can in itself pronounce a great sense of anxiety within anyone, Hitchcock was able to create a film that depended on its unpredictability.

It jumps from one character to another, one representation to the next, and keeps the viewer on their toes in apprehension for the next scene. Ominous voices, mysterious back-stories, and the complex “missing person” story line are mixed, baked, and served on a platter.

And for seasoning, Hitchcock was able to sprinkle not a dash, but a whole bowl full of cinematography that brings attention to the important detail of expressionism and sophistication.

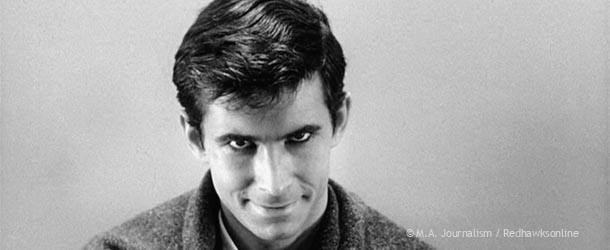

But let’s not give Alfred Hitchcock all of the credit. He may have directed the film, but he didn’t alone bring to life the infamous Norman Bates without the help of actor Anthony Perkins.

Norman Bates, a troubled psychopath, is similar to a modern day Dracula: while he’s charming and lustful, he’s also wicked and dark.

Who else was able to capture insanity into a gentlemen-like figure but Perkins, whose boyish face was able to convert from darkly handsome to sickly disturbed like the transformation of a cursed werewolf on the night of a full moon.

Released on DVD in 1999 with the classic black-and-white images of its age, “Psycho” has, regardless, still been able to brave against any oncoming attacks from newer and more technologically advanced films that wish to push it off its number one pedestal.