Tracing her path to a golden year

Fifty years ago, the average gas price was 39 cents per gallon. Fifty years ago, The Godfather won Best Picture at the Oscars. Fifty years ago, the Watergate trial was underway. Fifty years ago, the U.S. ended its involvement in the Vietnam War. Fifty years ago, Elaine Ekstedt began teaching at Minnehaha Academy.

In 2017, Elaine Ekstedt carried the mace as the faculty processed into the Benson Great Hall at Bethel University for graduation ceremonies. The faculty’s senior member traditionally carries the mace. Photo from Minnehaha Academy archive.

For a half-century, Ekstedt has been touching the minds and hearts of Minnehaha students, working as an English teacher, learning specialist, publications teacher, and resident historian in the school’s archive. Ekstedt’s legendary run at Minnehaha will never be replicated. To put it in very 21st-century terminology: Elaine Ekstedt is Minnehaha’s GOAT. That being said, it is only right that we give Ekstedt her flowers in her golden year.

In 1966, Ekstedt arrived at Minnehaha as a sophomore. One of seven children, she was the first of her siblings to go to the Academy.

“One of the reasons I wanted to be at M.A. was because I had friends who had Christian parents, and when I would go and spend time at their homes it was like, ‘Oh, this is what a Christian home is supposed to look like,’” she said.

During her 50 years as a Minnehaha Academy employee, Ekstedt has had many roles, as shown by her name badges and ID cards. Photo from Minnehaha Academy archive.

Ekstedt grew up in a Christian household and her father was very involved in the church, but there was a disconnect between the two environments. She attended a small church, where members got involved with church-related activities at a young age.

“I started playing the organ the summer after I graduated from MA,” she said. “I even played the guitar and led a little band.”

Covenant Pines Bible Camp and Minnehaha served as formational places for her as she made her faith her own.

“Covenant Pines is a place where a lot of kids have spiritual experiences,” said Ekstedt. “I had that there as well. However, I had a unique conversion experience.”

Ekstedt considered her conversion experience as happening in three separate stages.

“I had a conversion of emotion at Covenant Pines,” she said, with a laugh. “That’s where you get teary-eyed and everybody throws sticks in the fire.”

Some years later, Ekstedt returned to Covenant Pines as a counselor.

“This was the conversion of my mind,” said Ekstedt, “because this time I made the rational decision to follow Christ. It was more of a brain thing.”

However, through all of this, Ekstedt had never undergone one of the most critical sacraments of the Christian faith.

“My mother was a Christian Scientist, so we’d never been baptized,” shared Ekstedt. She wasn’t baptized until she was in her 20s and had moved out of her parents’ house.

“This was the moment when I said, ‘Okay, now I’ll give God my physical self,” she said.

Not everyone in her family shared the same journey of coming to faith.

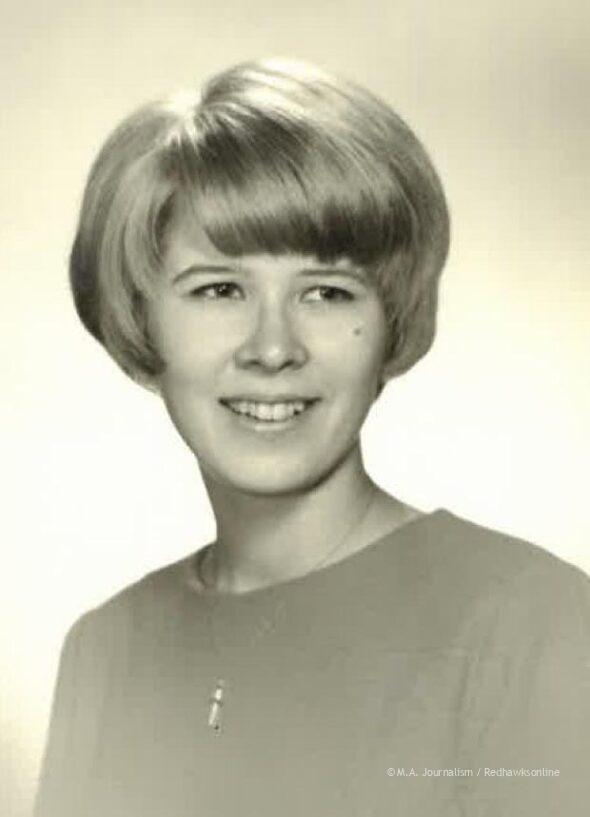

Ekstedt’s senior portrait in Minnehaha Academy’s 1969 Antler yearbook. Photo from Minnehaha Academy archive.

“Not all of my siblings came out with strong faith,” said Ekstedt, whose older sister attended North Saint Paul High School. “The late ‘60s were a tumultuous time. My sister would deal with constant bomb threats and racial strife.”

When she heard of Minnehaha, Ekstedt immediately wanted to go, despite having to take an hour-long bus ride to and from school each day. MA proved to be a great fit for the inquisitive Ekstedt. After graduating in 1969, Ekstedt went to Augsburg College in Minneapolis where she majored in English.

“Heading into college, I knew I wanted to be a teacher,” said Ekstedt. “I went to Augsburg mostly because M.A.’s counselor at the time had gone to Augsburg and was sending a lot of us over there.”

Despite being in a new environment at Augsburg, maintaining a Christian identity was something that proved difficult for Ekstedt and her high school peers.

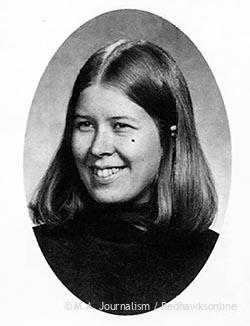

Ekstedt’s 1974 faculty portrait. Photo from Minnehaha Academy archive.

“About 15 kids in my graduating class at Minnehaha went to Augsburg,” she recalled. “About half of us survived college with our faith intact.”

Returning to MA

After graduating from Augsburg, Ekstedt returned to the classroom at Minnehaha.

“It’s the only job I’ve ever applied for in my life,” she said, adding that her application was completed entirely on paper.

Ekstedt was hired, but it wasn’t for the exact position she had in mind.

“I wasn’t hired to be a teacher; I was hired to be a faculty secretary,” said Ekstedt, which in those days meant running things off to the mimeograph (a sort of copying machine) for teachers.

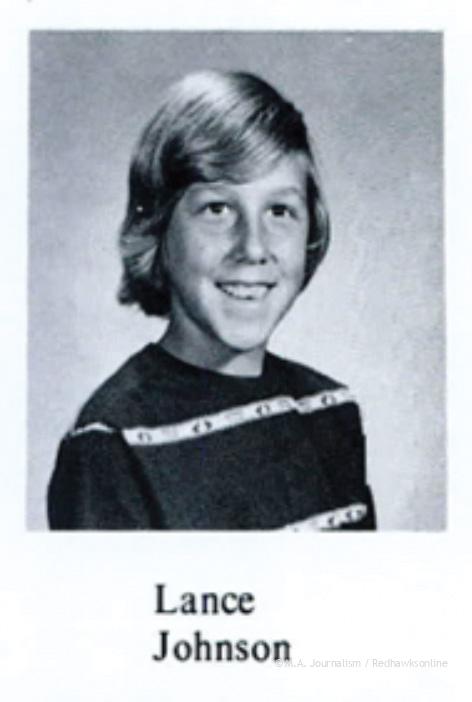

Lance Johnson, Minnehaha Academy’s Upper School dean of students, was in Ekstedt’s 9th-grade English class in 1974. Photo from Minnehaha Academy archive.

In the fall of 1973, Ekstedt came into her office two weeks before the school year started. Arlene Anderson, the principal at the time, called Ekstedt down to her office and asked her whether or not she was disappointed that she hadn’t gotten a teaching job. She proceeded to explain that Geri DeVries, one of the English teachers, had decided to take a sabbatical, thus leaving the position open for the 22-year-old Ekstedt.

“My entire life was rearranged in about half a day,” reflected Ekstedt. “I was standing on the edge and God came along and pushed me.”

Ekstedt’s first year of teaching was great. She walked into a tenured teacher’s position, taught six classes of English, had two preps and had her own room. This didn’t last for long though.

“My second year, I went down to the bottom of the barrel,” laughed Ekstedt. “I had all the classes nobody else wanted and had to move around to different rooms.”

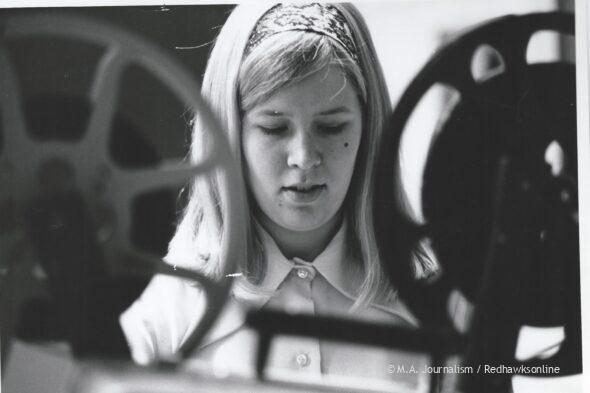

Ekstedt prepares a film projector for English class in the 1973-74 academic year. Photo from Minnehaha Academy archive.

Ekstedt kept teaching English, but in the fall of 1976, Anderson approached her once again with a new role: yearbook adviser.

“At that time, the yearbook was a club and the newspaper was a class,” she said. “When I assumed the new role, I had this wonderful little group of people who knew how to do the yearbook. The problem was that it was still a club. Deadlines didn’t mean anything and there was no grade.”

When the current newspaper teacher began losing interest in the class, Ekstedt saw an opening.

In 1981, Ekstedt working on an electric typewriter. Photo from Minnehaha Academy archive.

“I saw all these kids and I thought, ‘You have photographers. You have writers. You have people who can do layout and design. Why are you competing with each other?’ So I joined all of them together and created a program called Publications,” said Ekstedt.

In Ekstedt’s new class, everybody did everything. Photography, writing, and layout were all foundational skills that each student learned, but then they moved on to editor positions in their later years. But the process of making a yearbook looked very different 50 years ago.

“We did the yearbook on a quad pack,” said Ekstedt, which was four sheets of paper with carbon in between. “If you made a mistake, you had to go fix all the carbons underneath it.”

By 1986, Ekstedt could advise a publications student using an Apple desktop computer. Still, photography and layout in journalism had not reached the digital age. Photo from Minnehaha Academy archive.

The newspaper, then called the Quiver, was developed with similarly archaic methods.

“In order to make the Quiver, I typed the newspaper on an electric typewriter,” she said. “We had columns that were then printed for us which we laid out on boards and waxed out.”

At that time the size of the school was increasing.

“When I was a student at MA, it was 9th through 12th grade,” said Ekstedt. “When I came back as a teacher, they had added 7th and 8th. Then, they bought South Campus from Breck in the ‘80s.”

Minnehaha would become a preK-to-12 school, with the elementary and middle schools at the new South Campus.

A new role

With this growing change came a new need.

Very early on I started working with the kids who struggled,” said Ekstedt. “I liked these kids because they didn’t play games. They came in and said, ‘This is who I am. Take it or leave it.’”

When Ekstedt started in the English department, there was a tracking system that separated kids based on their proficiency in the field of English. Ekstedt enjoyed teaching the lower-track kids but wondered if there was a better way to understand and meet their specific needs, so she began researching learning disabilities.

In 2021, Ekstedt worked in a Learning Lab classroom wearing a mask due to the COVID-19 pandemic. She taught Learning Lab through the 2022-23 school year. Photo from Minnehaha Academy archive.

“I love puzzles,” she said, “and kids are like puzzles. Let’s figure out why they can’t learn and let’s do something about it.”

This approach paved the way for a class called Basic Skills. Ekstedt led this class with the aim of helping students conquer their learning difficulties.

“By the time the lower-track kids got to be seniors, they practically ran their English class,” said Ekstedt. “They had been together for so long, yet they hadn’t been exposed to higher-level thinking.”

Along with teaching Basic Skills, Ekstedt began to familiarize herself with the nature of learning disabilities. She went to the University of Minnesota and got a master’s degree in special education. In the fall of 1991, Ekstedt gave up Publications and took on the Learning Specialist position.

“I wrote my own job description and created the role itself,” said Ekstedt. “Everyone else was like, ‘Who’s this person, and why is she inserting herself into our school?’”

For the next 30 years, Ekstedt taught Learning Lab classes all by herself. However, the new century presented even more shoes for Ekstedt to fill.

Honoring history

In 2011, Minnehaha was getting ready to celebrate its centennial.

Ekstedt working in the school’s archive house in 2012. Photo from Minnehaha Academy archive.

“We realized that we needed something to commemorate the event, so [President] Donna Harris asked me if I would be in charge of the history committee,” said Ekstedt.

Responding to this new need, Ekstedt went to New Hampshire and took a class called Archives in the Schools from the archivist of Phillips Exeter Academy, a 200-year-old boarding school. When Ekstedt returned, the project went into full swing.

“We had this house over by the soccer field that wasn’t being used, and so we turned it into the Archive House,” said Ekstedt.

The Archive House was soon full of old Minnehaha artifacts that Ekstedt used to compile a book, which was written by her son, Justin.

“Now, the Archive House has taken on a life of its own,” she said.

Ekstedt visits the building every Monday afternoon with a member of her first yearbook club and a fellow graduate from ’69.

However, not only is Ekstedt focused on preserving Minnehaha’s past, but she’s also intent on observing her family’s history and looking to the future. Ekstedt’s grandmother was a teacher, and when she retired in the ‘60s she wrote a book called From Woodstoves to Astronauts.

“:In [my grandmother’s] book,” said Ekstedt, “she refers to the radio as being a dangerous technology. Then there were computers and those were definitely going to replace teachers. Still, time and time again, this new technology is harnessed and used to promote learning in innovative ways.”

Now that the age of Artificial Intelligence is upon us, Ekstedt plans to write a sequel titled, From Astronauts to Cyberspace.

“AI is just another tool,” said Ekstedt, “a tool that teachers can use to aid students in learning.”

Ekstedt is confident that AI will not overtake the teaching profession.

“Teaching will always be about the relationship between a teacher and a student,” said Ekstedt. “When a student wants to know something, and you as a teacher have the ability to show them how to do that, that’s magic. That’s why teachers teach.”

Elaine Ekstedt in the Minnehaha Academy archive house, where she will continue to work after 50 years in the classroom. Photo by James Wilson.

The impact that Ekstedt has had on the Minnehaha community is truly remarkable. Her willingness to step in and fill different needs embodies servant leadership in a beautiful, Christ-like manner.

“If you’re willing in your heart to let God use you, that’s the first step,” stated Ekstedt. “The second step is flexibility, because He may not want to use you in the way you think you are going to be used. You’ve got to be awake and aware. When doors open and close, you have to be willing to walk through them or not walk through them.”

Half a century of teaching excellence is no small feat. Yet more impressive, is half a century of humble attentiveness to God’s call. Life at MA from 1973-2023 has Ekstedt’s fingerprints all over. Minnehaha Academy will forever be grateful for Elaine Ekstedt and her 50 years as the greatest Redhawk in the flock.

50 years through the eyes of her colleagues

During her tenure at Minnehaha Academy, Elaine Ekstedt has impacted countless teachers. One of these faculty members is Robyn Westrem, a former English teacher and a current Upper School Teaching Librarian and Media Specialist. Westrem has been at MA for nearly 25 years and has witnessed Ekstedt’s innovative approach to teaching students with different learning styles.

“Elaine has always been a leader who is interested in innovation, specifically innovation in service of student learning,” said Westrem. “She finds ways for students who need another approach to the content or the skill.”

Westrem noted that Ekstedt has also been a great example for teachers, showing them how to come alongside students and foster learning.

“Elaine has always been a really optimistic and positive mentor for teachers in how to provide accommodations for students who learn in a different way,” said Westrem.

Serving students in this way requires flexibility and humility, two characteristics that have defined Ekstedt’s legacy at Minnehaha.

“She sees needs, jumps in, and starts learning,” said Westrem. “However, she doesn’t make it her own thing. She’s devoted to the things that she finds important, but she also invites other people to work along with her.”

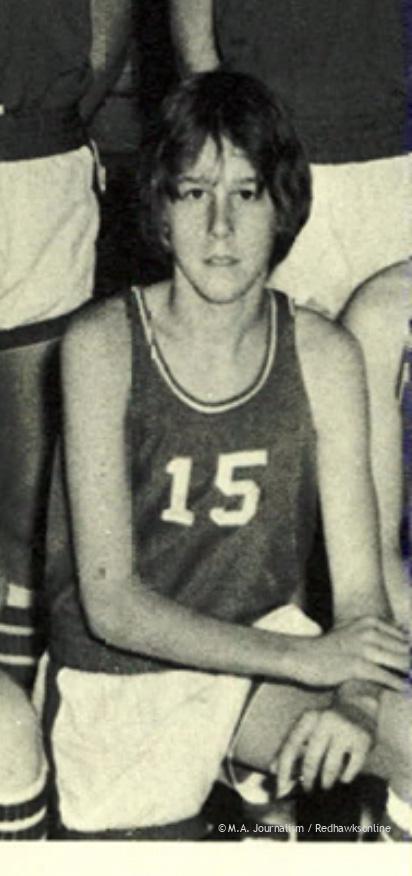

Lance Johnson, head coach for Minnehaha’s boys varsity basketball team, credits Ekstedt as the crucial force behind the organization and preservation of the school’s history, making it possible to find photos like this one, of Johnson as a member of the 9th-grade basketball team. Photo from Minnehaha Academy archive.

When Westrem started at the school in 1999, there was not much awareness of neurodiverse students and their needs in the classroom. Ekstedt was a trailblazer in the field of student learning, and always had a sense that there were approaches that teachers could take to help students see the subject matter from a new perspective.

“She has been ahead on so many of her projects,” reflected Westrem, “and her recommendations were always graciously delivered.”

However, while Ekstedt was keen on improving the lives of students through innovations in the classroom, she was also focused on preserving Minnehaha’s rich history.

“Her role as the school’s archivist is so important,” said Westrem. “She did so much work with the rebuilding of the North Campus because she was aware of what parts of MA’s history should be displayed.”

Lance Johnson, the dean of students and head boys basketball coach at the Upper School, also commented on Ekstedt’s groundbreaking work in the archives.

“We had little organization in terms of our school’s history,” said Johnson, “and she basically organized Minnehaha’s 100-plus-year history in a way that people can go visit and understand better. It’s something out of a college for Pete’s sake.”

In 2013, for Minnehaha’s centennial celebration, Ekstedt used her extensive historical knowledge to do intensive research for the book her son, Justin, wrote to honor the school’s legacy. Students and alumni can view the book, Minnehaha Academy: A Century of Faith and Learning, at the school’s alumni house.

Justin Ekstedt with his mother, Elaine, in 2012. The two worked on a book together covering the first century of Minnehaha Academy’s history. Photo from Minnehaha Academy archive.

“One of her biggest gifts is that she’s an organizer,” said Johnson, a skill that Ekstedt used not only to the benefit of the school but to the benefit of the student as well. “She took all this information about students with learning disabilities and organized it so that they were tracked and assisted from the minute they arrived at MA till the minute they graduated,” said Johnson.

In fact, Johnson has a unique perspective on Eksedt’s historic run because he’s witnessed it as both a student and an administrator. Johnson was a freshman at Minnehaha in 1974 and had Ekstedt as his English teacher.

“I remember her as a very good young teacher. However, I feel bad because I was kind of a squirrely student,” Johnson laughed, “so this is kind of an apology fifty years later.”

Elaine Ekstedt represents Minnehaha’s mission in a beautiful way.

Elaine Ekstedt represents Minnehaha’s mission in a beautiful way.

Ekstedt’s love of Christ and learning are foundational to her life and consequently affect everything she does. She has been a crucial member of the Minnehaha community for the last fifty years and the school is extremely fortunate to have had her innovative mind and thoughtful spirit grace the halls of 3100 West River Parkway.

In the video below from February 2020, listen as journalism students Michael DiNardo and Dylan Kiratli interview Ekstedt about the changes she has seen in student journalism during her years at Minnehaha Academy.

Elaine Ekstedt’s Journalism Era from Redhawksonline on Vimeo.