A different option for the terminally ill

“My dad was really the most amazing person,” recalled 16-year-old Elena Zeballos. “He was so full of life and could make friends with anyone — he knew half of Dallas!” She paused, then continued with a smile, “He loved his soccer. He loved any sort of sweets. He loved music.”

Although a renowned doctor specializing in physical medicine and rehabilitation, Elena’s dad, Pablo, had a whimsical side that dreamed of playing the part of Mother Ginger in the Nutcracker and fanaticized about working as a disc jockey at a radio station.

Elena laughed a bit as she continued, “Right before COVID hit, we actually got him into a DJ school…he had already picked out his name, DJ CIG.” She went on, “You are probably wondering what DJ CIG stands for? He was working for this patient, and the patient was coming out of anesthesia and told the resident, ‘You know, Doctor Zeballos reminds me of a chiseled Inca God.’ After that, they called him CIG at the office, and he wanted it to be his DJ name, too.”

A few weeks after DJ school was supposed to start, Pablo was rushed to the hospital in the middle of the night. When Elena and her family heard the diagnosis-Glioblasblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer-the world went quiet.

A downward spiral

As Elena, her younger brother, and her chronically ill mother stood in shock, the doctor explained that Glioblastoma is almost always terminal.

“There was 5% survival rate,” said Elena.

Although the Zeballos family could not have what they really wanted-to go back in time and erase the diagnosis-they found themselves having to grapple with unfathomable options: fight to extend Pablo’s life to Christmas, minimize Pablo’s unnecessary suffering, keep Pablo at home as long as possible, or search for alternative or untested treatments. What the Zeballos family and many others in similar situations do not fully appreciate is that the full range of options available to their loved one depends almost entirely on where they live.

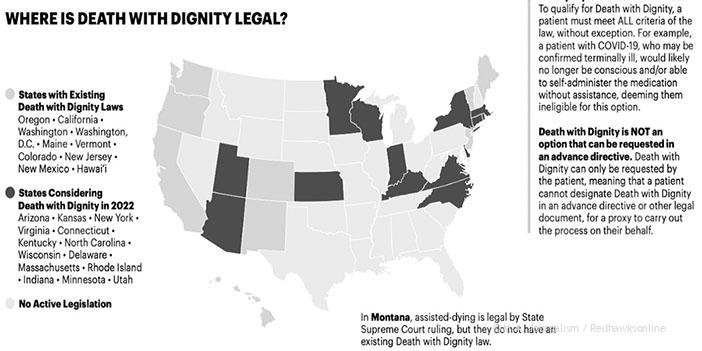

One option, available in some places, has many names: Physician Assisted Suicide, Physician Assisted Death, Medically Induced Suicide, Medical Assistance in Dying, Medical Aid in Dying, or Death with Dignity. It differs greatly from traditional end-of-life care or hospice. Hospice teams provide care for the patient throughout the final stages of disease but do not hasten death. In contrast, if a patient decides to hasten death through medical aid in dying, the doctor prescribes an intentionally lethal overdose, with instructions on how to use the pills to cause death. Texas, like Minnesota, has not yet legalized Physician Assisted Suicide.

Following the initial diagnosis, the Zeballos family decided to do everything in their power to help Pablo live for as long as possible, but even the limited time they had together was difficult. For the next year, Elena watched her dad die.

Elena describes life at home following Pablo’s diagnosis: “He wasn’t as sharp. Like, he still had some heart in there, but his heart was… a shadow of what it once was.” “We always had huge fights over what he could eat. He was always very adamant, very opinionated, and he became very aggressive.”

As her dad got sicker, his illness began to consume more and more of her daily life. His need for care increasingly robbed Elena of the ability to sleep and impacted her ability to go to-or even prepare for-school.

“He was taking like 30 pills a day, which I know because I would just sit with him and watch him take them one-by-one. It would take an entire hour. [I would tell him] ‘take your pills, take your pills.’ He just wouldn’t. He was so stubborn about it. It was just always a huge fight.”

Pablo’s death was a painfully slow one. With each passing day the bubbly, charismatic, witty father who raised her faded away.

“When he was more lucid he would talk to me, tell me ‘I’ll be here,'” said Elena, now crying. “‘I’ll be here for your graduation. And your marriage. And your children.'”

For Elena, the word difficult doesn’t even begin to encapsulate what Pablo’s last few days were like. He lost his ability to function, until the person left lying in the cold hospice bed was unrecognizable, even to his own daughter.

Pablo passed on April 24, 2022. Once again, the world went quiet.

Physician Assisted Suicide: controversy and legal implications

Physician Assisted Suicide was developed with the hope of helping patients and families in situations similar to Pablo’s. Many argue that this practice gives the terminally ill back just a sliver of autonomy over their lives, which are so often controlled by one thing only-illness.

“There is a big difference between this and suicide,” notes Minnesota Senator Chris A. Eaton who first attempted to introduce a medical aid in dying bill to the Minnesota legislature in 2015. “This Medical aid and dying [applies to] someone who would rather continue living but doesn’t have that option.”

Ten states have passed medical aid in dying bills similar to that proposed by Senator Eaton: Oregon, California, Washington, Hawaii, New Mexico, Colorado, Montana in the West, Maine, New Jersey and Vermont in the East– plus the District of Columbia. There have been no real issues surrounding the enforcement of these bills in states that have passed them. “There have been no lawsuits…or reports of violation” related to the Medical Aid in Dying law “in California and Oregon” where Physician Assisted Suicide is legal, Senator Eaton noted.

Despite Senator Eaton’s proposed bill, today Minnesota still prohibits Physician Assisted Suicide.

“Most physicians are neutral or support this, I’d say about 75% of people in Minnesota right now support it in some form. Essentially you have the pope, evangelicals, and anti-abortion leaders [aginst Physician Assisted Suicide],” concluded Senator Eaton. But, Senator Eaton continued, “If we want this bill to pass, we need democrats. There is nobody who can get elected as republican who would support this bill.” Senator Eaton further explained that what happens with this bill in Minnesota “depends on what happens on November 8th. It really does.”

Despite Senator Eaton’s suggestion that there is vast support for her bill, Schniderhan, a pharmacist and associate professor of pharmacy practice and pharmaceutical sciences at the University of Minnesota, has concerns about logistical and moral issues related to Physician Assisted Suicide. According to Schniderhan, pharmacists “don’t know when we are setting orders up on the floor [that they are orders to aid someone in death,] we assume they are to help the patient.”

Regulations and laws related to Physician Assisted Suicide take some of the critiques into account. In fact, in many states, and in Eaton’s proposed bill, to qualify for Physician Assisted Suicide, patients must have a terminal illness as well as a prognosis of six months or less to live. A mental health screening is also required. Schniderhan, though, touches on the deep rooted flaws in the mental health screening system.

“We need to do better screening [for mental health.] It’s really an art. If someone is really struggling they are not just going to tell you up front. It does take some time, not just a PHQ where they can check the boxes,” said Schniderhan.

Further complicating the utility of mental health screenings is the inevitable overlap between chronic illness and mental health disorders: after all, about 1 in 4 cancer patients also have clinical depression.

Senator Eaton disagrees with Schniderhan’s concern, “I’m a nurse, I’ve worked with people dying, and contrary to popular belief not everyone dying is depressed. They come to terms with it and the transition can be very peace-

ful. Every person is different.”

In the end, it seems that states where Physician Assisted Suicide is legal, have opted to resolve the debate by putting the power in the hands of the patients and their families. Elena would have appreciated this power during her dad’s final months.

“I see why people do it [Physician Assisted Suicide], sometimes I wish we at least had the choice…to see what my dad would have wanted anyway,”concluded Elena. ” I wanted CIG to be his DJ name, too.”