Taking democracy for granted, young Americans can learn from Soviet era

Imagine living in a country where the view to neighboring countries is blocked by high electric fences. You cannot be sure who you can trust, because anyone, even your friend, can be a spy. You can’t talk about controversial topics in public spaces or on the phone because you could be wiretapped.

Younger generations that haven’t experienced living in a non-democratic country often misunderstand the reality of living under a totalitarian regime. Statistics published by The Open Society Foundation stated: “Just 57 percent of 18-35-year-olds think democracy is preferable to any other form of government, compared to 71 percent of older respondents.” Gen Z is the generation that shows one of the highest support levels for dictatorship, believing that totalitarianism can even be beneficial under certain circumstances.

I am from Slovakia, a country that gained democracy and freedom only 35 years ago. Before the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, Czechoslovakia experienced communism, a type of totalitarianism, for 41 years. Until this day both the Czech Republic and Slovakia (which split at the end of 1992) have had to deal with the consequences of the former regime.

Czech and Slovak members of Gen Z, the first generation who didn’t experience communist Czechoslovakia, are very well educated on the country’s time of totalitarianism because the older generations are aware that people who forget history tend to repeat its mistakes. The majority of American Generation Z or their families have never directly met with a totalitarian regime and often misunderstand the reality of it.

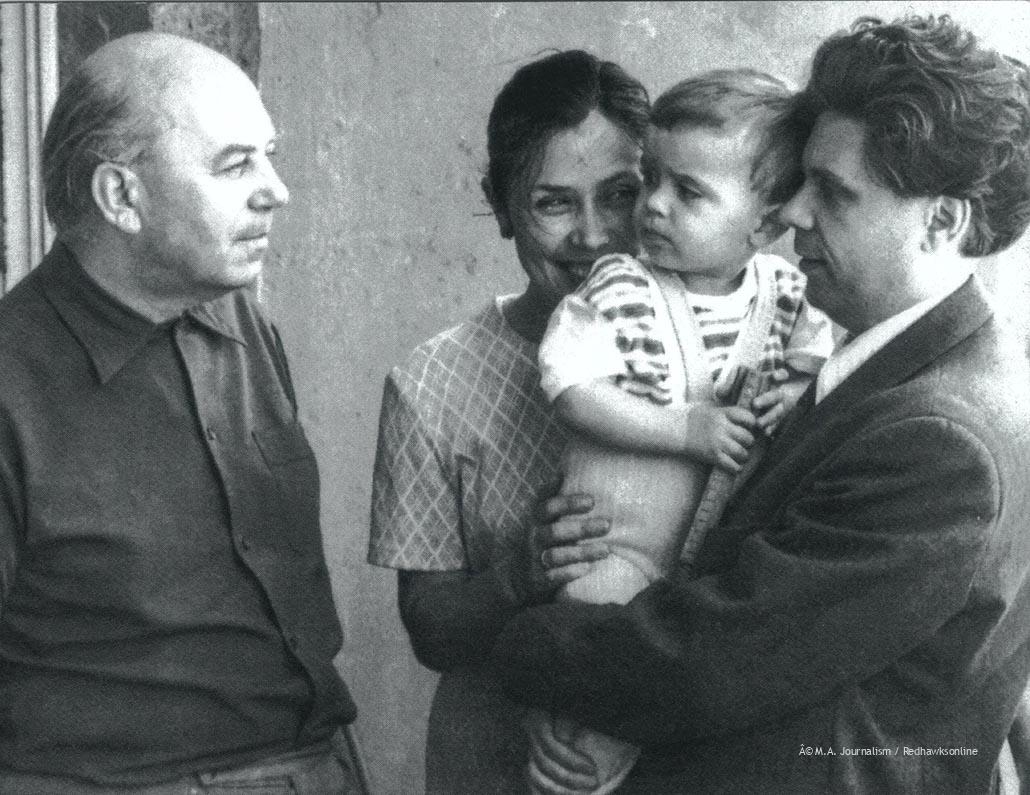

My whole family was heavily affected living under communism; their stories made me realize that something as simple as freedom of speech or religion is not guaranteed. By sharing the stories of my family, I hope I may help you realize the value of democracy and the freedoms that come with it.

My great-grandfather, Jozef Zavarský, who was politically active and was the first managing editor of a revived Catholic newspaper, was falsely accused of being a Nazi by the Communist Party after WWII. His brother, Aurel Zavarský, was persecuted as well by communists, not because of any false accusation but because he was a Catholic priest. He was sentenced to do hard labor in uranium mines, which destroyed his body and impacted the rest of his life.

Why was my great-grandfather falsely accused? The Communist Party simply wanted to find people to blame for the critical post-war situation in Czechoslovakia and prevent any resistance against the regime. These “enemies” of communism were often people who didn’t hold communist beliefs and opposed the Communist regime. For example, they were openly religious in an officially atheist Communist nation.

After being held in prison for one year on death row, my great-grandfather was released because of a total lack of any evidence for his connection with Nazi regime. Despite the lack of any evidence, he and his family continued to be persecuted. They had to move from city to city a total of 13 times, living on the edge of society, often living with other falsely accused “enemies” of Communist Czechoslovakia.

Although my great-grandparents were both highly educated, they had problems finding a job, leaving my great-grandfather, great-grandmother, and their four kids often hungry. They didn’t have enough money for food so they had to hunt wild pigeons so they would have at least something to eat.

Because of the persecution, my great-grandfather had to quit his job as a journalist and could find work only in poorly paid manual labor jobs.

Later, his son, my grandfather, Jozef Zavarský, Jr., followed in his footsteps and became a journalist. Even though my grandfather had nothing to do with the false accusations against his father, Communists used generational punishment, which means that descendants of a “criminal” would be punished for earlier family “crimes”.

My grandfather struggled to get higher education because many schools rejected him for political reasons. After he completed one successful semester studying college-level nuclear physics in Bratislava, Communists told him he could no longer attend the university due to political reasons and prevented him from getting any higher education anywhere else.

During his career as a journalist, he was openly religious, and from 1985 to 1989 he was part of an illegal newspaper called Family Community which encouraged Christians in Czechoslovakia to not give up on their faith.

“The members of the Family Community newspaper were meeting each time in different places,” my father, Andrej Zavarský, the son of Jozef Zavarský Jr., told me. “Each meeting was hosted in the houses of the members, and the place of meeting had to be somewhere else each time so it wouldn’t be suspicious.”

He explained that he was a teenager when his father was part of this Christian newspaper, aware that he could end up in prison if the Communists found out.

“My brother and I were growing up in a double-consciousness state of mind, where we heard something different in school and something different at home, and what was said at home couldn’t be shared with anyone else,” he said. “We were growing up as Christians at home, but we were forced to stay silent about it in the outside world.”

Growing up religious in a Communist country meant that you couldn’t profess your faith in public unless you wanted to deal with the consequences. Kids in schools were forced to write anti-religious slogans in their textbooks, such as “God does not exist,” and if they openly admitted they were religious, some teachers didn’t hesitate to bully them or use physical punishments such as beating their fingers with a ruler.

My father, representing the third generation of a persecuted family, still had to deal with the consequences of my great-grandfather’s “anti-regime crimes.”

“When I was applying to high school after I successfully did the entrance exam, Communists came to the school to talk with the principal and tried to persuade him to not let me study at the school because my grandfather was anti-Communist,” he said. “They tried to take the education from me as they did from my father. Thankfully the principal was helping kids who came from families seen as enemies of the regime and let them study there.”

My siblings and I understand that if the Iron Curtain had not fallen, we would also be living on the edge of society, and the education we have would be just an unreachable dream. I certainly would not have been given the permission to leave the country and study in the United States. Living in a totalitarian country means that just because you are seen as an enemy you will be punished, and if you are related to someone who is seen as an enemy you also will have limited options for education and job opportunities and will be excluded from society.

You can’t speak up your mind if it goes against the regime, and if you hope your kids will have a better future you have to stay silent, blindly agreeing with whatever the government says.

Living in a country that guarantees freedom of speech and religion is a privilege, and even in the 21st century it’s not guaranteed for all of the countries in the world.

Gen Z can use history to learn from past mistakes and prevent the dark past from repeating. Unfortunately, the opposite can happen too: history shows us that citizens living in democracies can embrace totalitarianism and give away their freedoms.