A local police officer, judge and teacher discuss how to keep implicit bias from affecting how people treat each other

Blink. It takes one third of a second to blink. It takes one third of second to size up an individual, an unconscious perception in the blink of an eye. In the span of 10 seconds, the unconscious mind has registered its surroundings and filed them into their respective folders in the brain.

Teachers and students enjoy the different cuisines at the “Courageous Conversations” event.

Implicit bias, or the mind’s “blink,” is the immediate perception the brain creates based on the variety of experiences each individual sees throughout their life.

Minnehaha President Donna Harris recently quoted Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink in the introduction of a MOSAIC event March 28. The event was a part of a series called “Courageous Conversations,” targeted towards breaking through implicit bias.

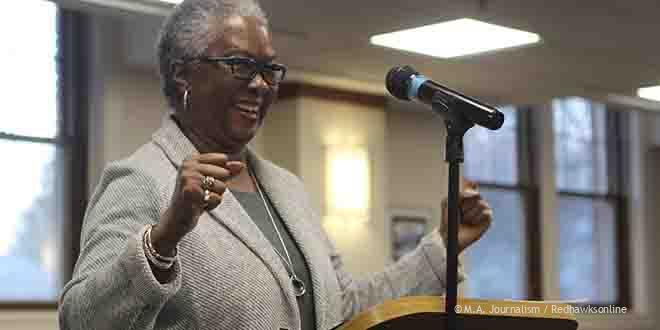

Judge Pamela Alexander speaks at MOSIAC’s “Courageous Conversations” event about her experiences in the juvenile criminal justice world.

Pamela Alexander, a local judge, spoke about her own personal experiences of implicit bias in the criminal justice realm, focusing on sentencing disparities and juvenile court.

Implicit bias is an unconscious bias found in each and every person, across all occupations, whether it be from the justice to the education system.

While implicit bias is not inherently bad, it can negatively influence stereotypes if unchecked. In order to de-bias, one must immerse themselves in new experiences, thus creating a self with less prejudice.

Gladwell discusses implicit bias in his book Blink, emphasizing the power of the unconscious mind in everyday situations. He describes the unconscious reaction as thin-slices, which constantly build up through experiences that translate into an implicit, or unconscious, bias.

“We don’t deliberately choose our unconscious attitudes…We may not even be aware of them,” Gladwell writes. “The giant computer that is our subconscious silently crunches all the data from the exper

iences we’ve had, the people we’ve met, the lessons we’ve seen, and so on, and it forms an opinion.”

An increasingly common way to “diagnose” implicit bias is in the form of the Implicit Bias Test (IAT), created by Project Implicit.

The program has a variety of sectors in which to test for implicit bias, such as correlation between gender and careers as well as “good” or “bad” words with black or white people.

Commonly, test-takers report a relative link between family with females and male with careers, or discover that most Americans have a preference for white over black.

Senior Maddie Smith, who is African-American, took the race IAT and received a result of a moderate automatic preference of European Americans over African Americans. Smith revealed that she was not surprised by her result because of the predominately white environment of Minnehaha she has been a part of.

“I’m used to being the only person of color in my surroundings, so it is kind of unusual to see more people of color,” Smith said. “I have definitely found myself feeling more comfortable within a group of my white family rather than my family that is African American.”

The question that still hasn’t been addressed is ‘why?’ Why do most Americans have a preference for white over black, even if they actively believe both races are equal?

Gladwell expands on this topic throughout the chapters of Blink, and interviewed Mahzarin Banaji, an expert of the IAT test and psychology professor at Harvard.

“‘You don’t choose to make positive associations with the dominant group,’ she said. ‘But you are required to. All around you, that group is being paired with good things.'”

If implicit bias is something that everyone deals with, then that must mean the same bias can fog the lens of many professional careers, such as policing, delivering sentences as a judge or even teaching in a classroom.

Roseville Chief of Police Rick Mathwig expressed the importance of embracing the flaw instead of condemning the unconscious wandering each citizen or police officer has.

expressed the importance of embracing the flaw instead of condemning the unconscious wandering each citizen or police officer has.

“[The police department] recognizes that implicit bias is natural in people, and it is not wrong,” he said. “You need to recognize it is a part of the human condition, and make sure it doesn’t influence your decisions outside because everything needs to be fair and equal. Life isn’t fair or equal, but [police officers] need to apply the law equally and fairly.”

All Minnesota police officers undergo implicit bias training, in the form of two online courses that must be renewed every year. The courses are through the League of Minnesota Cities, and focus on recognizing implicit bias as normal.

On the other side of the spectrum, judges face their implicit bias every day, with each decision they make.

Alexander is a Hennepin County District Court Judge who specializes in deciding juvenile delinquency and child protection cases.

“Implicit bias is the type which we are acculturated towards by our attitudes and stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions and decisions in an unconscious way,” Alexander said. “This is especially important for judges who make decisions every day that affect people’s lives to have a healthy understanding of their unconscious bias and work to eradicate it to make fair and impartial decisions.”

With an average workload of seeing 150 people in an afternoon, Alexander is almost forced to rely on her instinct, but she still emphasizes the need to take a minute to process everything.

“We have developed an implicit bias bench card that reminds judges daily of what they need to do to make sure implicit bias does not creep into their decision making process,” she said.

More personally, Alexander reflects on her own biases, and how she works towards looking past it in her work.

“I am an African American woman, and I cannot separate who I am and how I view the world from my daily life as a judge,” she stated. “I can only understand where my life experience may play a role in my decision making process and be conscious of it.”

Implicit bias affects every level of the justice system, from the first interaction with the police officer, to the final ruling of a judge’s sentencing. The importance, however, is to not let any bias stay unchecked. On a local level, implicit bias can affect the way teachers interact with students everyday.

Diversity director Paulita Todhunter educates teachers about implicit bias and how to manage it.

“In the classroom, bias is seen in who gets called on, how a teacher arranges their classroom, or in the curriculum that is chosen,” Todhunter explained.

“I tell teachers that in a classroom, there are windows and mirrors. All kids should be able to see themselves, and all kids should be able to learn about other people in the classroom. If your curriculum focuses primarily on the dominant culture, that is because of your bias. If you’re not trained to see others, then it may seem as if they are not valuable.”

Although implicit bias is a natural tendency everyone faces, it is still possible to de-bias one’s self. Gladwell reminds readers in his novel that the same “thin-slice” of negativity can be turned into a positive experience just as quickly.

“Our first impressions are generated by our experiences and our environment, which means that we can change our first impressions…by changing the experiences that comprise those impressions,” he writes.

Each small positive first impression someone experiences with a different race is one step towards refocusing the unconscious mind.

“Think globally, act locally,” Mathwig emphasized. “Difference is what makes the world a better place. In the police station, make a lot of small investments into people and have those grow. Create positive contacts that grow.”