It’s 1957. An aspiring female author with boy-cut brown hair leans across a desk and offers a well-worked manuscript to Tay Hohoff, an editor at LB Lippencott. The editor fans through the manuscript’s crisp pages, digesting a story about a young woman named Scout.

It’s a story about right and wrong, about a loving father and his daughter, about racial prejudices in the American South. The novel has potential. But the storytelling is too fragmented, and the protagonist is too old. Hohoff asks the author to rewrite it.

Two and a half years later the author returns with a fresh manuscript. It’s titled To Kill A Mockingbird.

Published in 1960, Harper Lee’s first novel was embraced as an immediate classic. To Kill A Mockingbird was deemed “Best Novel of the Century” in 1999 by the Library Journal. It won a Pulitzer Prize in 1961, was produced into an Oscar-winning film in 1962, and has been taught in school curriculums for decades.

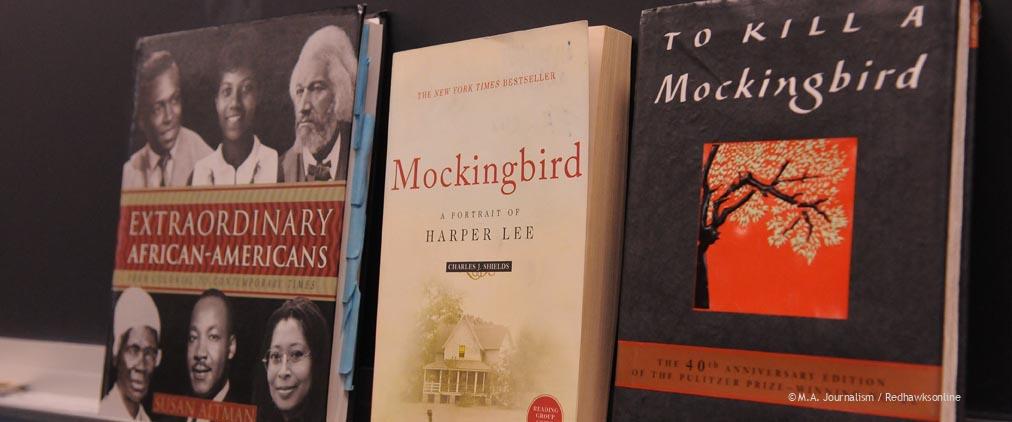

However, it stands alone on American shelves as the only book with ‘Harper Lee’ etched on its spine. Lee never published a second novel. The single literary masterpiece she left on American doorsteps left a legacy of indisputable talent.

“She was lucky enough to have captured many of the things she most wanted to replicate her first time out,” biographer Charles J. Shield wrote in Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee. “Many writers have done much less after many books. Maybe she was, in some sense satisfied. Maybe her deed was done.”

However, Lee is not done. On July 14, a new book will join To Kill A Mockingbird in Lee’s collection of works. At the age of 88, Lee is publishing a second novel titled: Go Set A Watchman. It’s the same manuscript that Tay Hohoff handed back to her over 50 years ago, the one she was asked to rewrite.

Lee thought the manuscript was lost until last summer, when her lawyer found it amongst other paperwork.

“I hadn’t realized [the original book] had survived so I was surprised and delighted when my dear friend and lawyer Tonja Carter discovered it,” Lee said, in a statement released by Carter. “After much thought and hesitation, I shared it with a handful of people I trust and was pleased to hear that they considered it worthy of publication. I am humbled and amazed that this will now be published after all these years.”

In Go Set A Watchman, Scout visits her father Atticus in her hometown of Maycomb, Alabama. It’s been 20 years since the trial of Tom Robinson, and adult Scout remembers childhood events through flashbacks. In 1957, Tay Hohoff denounced these flashbacks for Lee’s storytelling, and little has been edited between the original work and published work of Watchman. This causes doubts towards the book’s potential.

English teacher Phil Erickson has analyzed Mockingbird with eighth graders for almost a decade and has a deep adoration for Lee’s classic novel. Erickson sets lower expectations for Watchman.

“There’s more of a chance of it being disappointing than not being disappointing,” Erickson admitted. “When you think something is so cool and so good for over a period of years, you think ‘How could anything compare to it?’ I’m thinking I’ll really like [Watchman], but expect it to be slightly disappointing.”

Similarly, 11th grade English teacher Katherine Myers wonders if a subpar sequel to Mockingbird could tarnish her perception of the great classic itself. She pointed out that successful authors often write books other than their widely-acclaimed wonders.

“We admire The Great Gatsby so much that the other texts like This Side of Paradise are sort of lost in their ability to connect,” Myers claimed. “But [they don’t] seem to take away from The Great Gatsby.”

It isn’t until an author adds a subpar sequel to a classic, that Myers questions credibility. Myers applies this concept to the publishing of Watchman, afraid that the sequel will affect her perception of Atticus.

“The worry is stemming from the love of these characters,” she explained. “I know Atticus Finch so well and I admire everything about that humble man, loving father, devoted citizen. What if he missteps [in Watchman], what if he disappoints? If Atticus Finch isn’t the hero that I’ve known for all 33 years of my life, then what am I going to do? Am I disappointed in her novel because there’s a character that she tarnished or changed?”

Though Myers’ questions can be answered only after reading the anticipated book, it is fair to conclude that Go Set A Watchman will be used to further understand To Kill A Mockingbird.

It may not stand as a classic itself, but it will be analyzed down to the last word because it is the rough draft of a classic.

In 1945, The New York Times reported on what they claimed to be “the most important literary event of the year.” This article wasn’t about the publishing of a new book but rather, about the publishing of James Joyce’s first draft to his famous work of A Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man. This draft was called Stephen Hero, and it gave the literary world the prominent gift of comparison.

The Times wrote, “It provides also invaluable laboratory material for anyone interested in the technique of the novel.”

By comparing Stephen Hero to its successful relative, readers were able to distinguish what the author changed from rough to final draft. In this way, Joyce’s prevailing message was emphasized. His intentions were highlighted, his process understood. The world was able to learn by watching the author revise.

Maybe that’s what Harper Lee will give to her readers: an understanding of the process, an emphasis on a prevailing core. It’s not about whether Go Set A Watchman can compare to To Kill A Mockingbird. It’s about realizing what she did to create a masterpiece. Despite anticipated disappointments, the literary world should rejoice. Harper Lee is once again leaning across a desk, offering the well-worked manuscript in her hand.