Words meant to entertain may be more hurtful than humorous

“I was in my living room eating dinner by myself when the fire alarms went off. I was going around the house unscrewing them because I didn’t smell smoke. I called my dad and said, ‘Yeah, something’s wrong’ and he said, ‘Did you check all the rooms?’ I opened the door to my basement and there was a huge cloud of smoke. Before I knew it, my house was on fire.”

With distant eyes, senior Andre LaRenzie recalled the vivid April evening.

“Within 15 minutes, pretty much everything went up in flames. I got out of the house and called 911. There aren’t any fire hydrants in [Afton] so it took a good 45 minutes to get the water trucks out there. Everything was pretty much burned down by then. [The firemen] went in first and deemed that the house was could not be saved. I was in shock more than anything.”

One year ago as of this Sunday, a boy who was left home alone stood with his heels to the curb: his world left in ashes and uncertainty.

Nine months later, a phrase about flames was used during business class.

“Steve Jobs was told that if he didn’t do a certain thing, he wouldn’t be successful: at which point he dropped out of college,” senior Griffin Pontius explained. “As a joke I said ‘Ten years later, he bought the college and burned it down.'”

“I honestly didn’t take offense to it,” LaRenzie remembered smiling. “I just like to mess with that kid. So I said ‘Buildings burning aren’t funny to joke about.'”

“At first I had this mortified realization of what had happened to him,” Pontius said shaking his head.

Noticing his classmate’s discomfort, LaRenzie quickly explained that his response was a joke. The boys joined in laughter.

Though the two reacted with pats on the back, Pontius realized his remark had the potential to trigger painful memories.

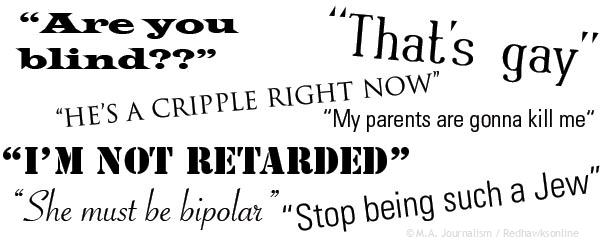

LaRenzie and Pontius are not the only students conflicted with humor’s undefined boundaries. High schoolers face comedic slurs, stereotypes, and slips of the tongue in the hallways and at the lunch tables everyday.

Shown by LaRenzie, who’s marked with traumatic visions of fire, levels of comfort are rooted in personal experiences.

Witnessing it firsthand

“A woman at my work suffers from depression, alcoholism and is bipolar. Recently she’s been having meltdowns at work,” senior Sophie Gunderson stated. “She came into the office one day and just sat on the floor and cried. She said ‘I can’t be here, I can’t work here anymore, I’m so sad, I can’t be here.’ She couldn’t drive, she didn’t want to call home. You think that these things just affect younger people. But she has a family, she’s married, she has children at home.”

Gunderson continued, acknowledging that topics like depression and alcoholism are subjects of derogatory jokes.

“I feel sensitive toward mental illness jokes because I’ve seen it and witnessed it firsthand. Mentioning [depression] in a way that makes the person suffering seem weak or broken really bothers me because they’re not weak, they’re just chemically imbalanced. I don’t think people understand that it’s not something you can control.”

Lack of understanding

Many of Gunderson’s classmates are unaware that her memory is etched with an image of a co-worker collapsed on her knees in desperation.

Students find this lack of awareness as the cause to most insensible jokes. Sophomore Johnny Goth realizes that students don’t consistently recognize their classmates’ personal backgrounds.

“People will make ‘yo mama’ jokes and there’ll be a person sitting at that lunch table that doesn’t have a mom, or their mom passed away a few years ago,” Goth explained. “You see everyone laughing but you look at the other person and they’re just straight-faced.” Goth paused, contemplating. “You can’t always know everything about people, which is why it’s hard.”

“That’s why people joke about it,” sophomore Britta Chelgren reflected. “They don’t know the complexity of it.”

Chelgren remembers her own tears and of others trembling on her shoulder.

“When I was in a bad state, I’d think ‘What’s the point of getting through this when someone’s just laughing at it?’ I understand that people don’t mean things literally and they’re not attacking it. I give them the benefit of the doubt,” she expressed cautiously. “But it still is offensive. At certain moments it brings me back to how painful it was. It digs deep. It’s ironic because they’re laughing but for me it brings up [unhumorous] memories: the opposite of what they’re trying to convey.”

“A lot of the time it’s off the top of your head, the first thing that comes to mind,” sophomore Grace Diersen explained. “That’s what makes it a funny moment. We all laugh about things like that from time to time,” Diersen admitted. “Just in the end, we don’t know who it’ll hurt.”

So how do teenagers attain awareness and avoid hurting people with humor? Students discover their own approaches.

Choosing your topics

Senior Hayoung Lim decides to avoid making jokes about unfamiliar topics.

“You need a reason to be making a joke on that topic,” Lim stated. “I don’t feel comfortable with making jokes about African-American people because that’s not my community. If I grew up with it and it was almost a part of me: the culture, the background was so heavily connected to me, then maybe I could see [myself joking about it]. But I don’t know much about it. That’s just how it is, so I don’t feel like I have the right to make jokes about it.”

Educating your peers

Johnny Goth decides to quietly correct insensible remarks by spreading awareness and sympathy for his classmates.

“You should pull the [joke teller] to the side when no one else is around and say ‘Hey, you probably shouldn’t have said that, I can only imagine how this kid felt’,” Goth suggested. “That makes the joke teller feel bad, which is sometimes needed to make them think about what they’re going to say.”

Discussing your limits

Another approach to understanding comedic boundaries is to discuss what you’re comfortable with. LaRenzie vocally defines his own line between what’s funny and what’s too close to painful reality.

“If I don’t really know you, I would hope that you would never make a joke about it around me, I would take a lot of offense to it,” LaRenzie reflected about the night of the fire. “I have really bad nightmares about it. There’s not really a day where I pass where I don’t think about it, about how much it affected my life. But if it’s one of my main friends and they joke about it, they understand where I came from and what happened and how much of a toll it took on me. They’re definitely eligible to make jokes about it.”

So whether students decide to select familiar topics, empathize, or discuss their boundaries, may they also remember what humor is supposed to do.

“Laughter’s the best medicine and it’s cliche but it’s true,” art teacher Nathan Stromberg expressed. “It’s what gets you through your day. I use humor as a way to break down barriers and to make things light-hearted and fun.”

While students may be drowning in mental illness, family loss, or race, LaRenzie’s visions are engulfed in fire.

Instead of using humor to break down barriers as Stromberg mentioned, LaRenzie and Pontius discovered comedic common ground: a landmark within both their boundaries.