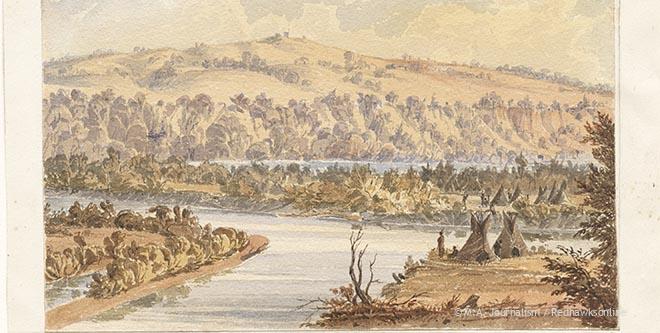

Minnehaha finds a temporary home near the confluence of rivers

A familiar winding road follows the twists and turns of the Mississippi. Below, the river gradually meanders south, where it eventually meets another waterway, the Minnesota River. This meeting of the rivers is called a confluence, and the Dakota word for this is ‘bdote.’ Just above where the two rivers meet, a historic fort sits tucked among the trees on the northern shore, while a sacred hill stands opposite on the southern bluff.

As a mob of cars flows across the Mendota bridge, the area’s significance is quite literally passed over. But, for many Native Americans, specifically the Dakota, this area is special. It is considered the center of the world.

“According to our oral tradition, [the confluence] is the place where Dakota people were created or where we came to live on the earth,” said Iyekiyapiwin Darlene St. Clair, an Associate Professor of American Indian Studies at St. Cloud State University who also has Dakota heritage. “It’s a confluence of the Minnesota and the Mississippi rivers. We call the Minnesota River the ‘Mnisota Wakpa’ and we call the Mississippi River the ‘Haha Wakpa.’ The first Dakota man and the first Dakota woman emerged out of the earth at that place. That’s not the end of the story, but that’s our beginning.”

The confluence of the rivers is deeply connected to Minnehaha, as a hallmark of the school has always been its location on the Mississippi River. After the explosion on August 2, Upper School students were forced to relocate to what was seemingly a mundane office park in Mendota Heights, a stark contrast with the scenic view of the river that the North Campus provides. However, the Mendota area is rich in history, both to Native cultures and early settlers, and while the Mississippi River has been home for Minnehaha for over a hundred years, the current location near the Minnesota River, as well as the important connection between the two rivers, is worth noting.

“Dakota girl at Mendota,” photographer unknown, approx. 1880.

“The confluence of those two rivers is a really important place in Dakota myth,” said Carleton professor of Native American religious tradition, Michael McNally. “[Some of the Dakota believe] their people descended from the stars on the bluffs above the Mississippi River. It’s their Eden, their place of origin, a place for sacred stories to connect to.”

Currently, Minnehaha’s Upper School is located in Mendota Heights, a city located on the east bank of the Mississippi river, just a few miles from the confluence. After the native peoples, the first settlers in the area were French and British fur traders who established the region as an important center for trade and opened an American Fur Company post in 1825. Among these individuals was Henry Hastings Sibley, a fur trader and army general who went on to become the first Governor of Minnesota, and for whom both Henry Sibley High School and the city of Hastings were named. Historic Sibley House is located less than three miles north of Minnehaha’s Mendota Heights location. Today, Mendota Heights is a city that remains rich in Native American history and is filled with landmarks that are still considered sacred by the Dakota people.

Another landmark in the Mendota Heights area that is considered sacred by the Dakota people is Oheyawahi, the hill on the east bank that looks over where the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers converge. For the Dakota, Oheyawahi, which translates as “a sacred place much visited” was originally used as a burial ground and gathering place for ceremonies. When burials took place, the Dakota would place their deceased relatives on scaffolds before burying them.

Seth Eastman, “Dakota Graves at the mouth of the [Minnesota River],” watercolor, 1847. The painting above depicts the traditional scaffolding that the Dakota people would place their deceased relatives on before burying them in the earth on the sacred hill of Oheyawahi/Pilot Knob. Photo courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society.

“The hill there is a place laden with a history of ceremony,” said McNally.

In the early 1800s, steamboat traffic in the area started to become prevalent due to the trading post established at Fort Snelling. Steamboat pilots used the hill as a landmark as it was easy to pinpoint, thus leading to it being named Pilot Knob. The hill was also the location where the 1851 Treaty of Mendota was signed, which essentially led to the Dakota people ceding much of their land in southeastern Minnesota to the United States government. Today, Pilot Knob is still sacred to the Dakota people.

“When you visit those places you can feel the sacredness, and I think that’s important,” said Minnehaha sophomore Sita Baker, who has Dakota heritage. While Baker said that she has never visited Oheyawahi/Pilot Knob herself, it is an important sacred site for her mom.

In 2006 and 2007, the City of Mendota Heights purchased a total of about 30 acres of land along the southern bank of the Mississippi river in order to protect Oheyawahi/Pilot Knob. Today, the hill is preserved by the City of Mendota Heights as an Open Space site, where a monument of seven limestone blocks exists to honor the seven Dakota/Nakota/Lakota groups whose members live across the west and midwest.

Sadly, though these sacred sites still exist, the landscape is drastically changed from when the Dakota people first called the land home. European settlers colonized the land in the 1800s, and today, surrounding the confluence of the rivers is a booming metropolitan area home to busy roads, the MSP airport and loud traffic.

“There’s no pretending that this is not a site of colonization,” said St. Clair. “For Dakota people, it’s an interesting circumstance of having some of our most sacred sites [have] a huge metropolis get built on top of [them]. Some elders would say that it is because of the power of that place that has drawn other people [there] as well.”

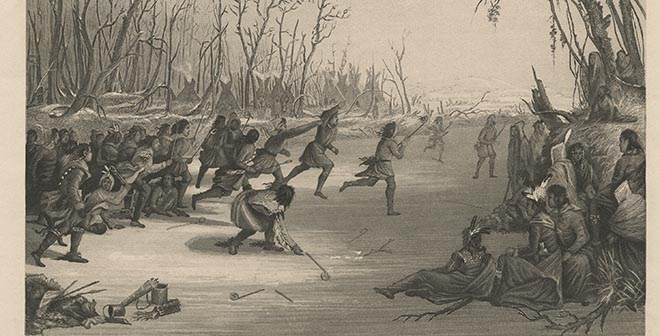

Seth Eastman, “Ball Play of the Dakota Indians,” engraving, 1850. Photo courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

McNally described what it is like to visit the Pilot Knob preservation site and look out over the river and surrounding area.

“You can see the airport, Mendota bridge, downtown Minneapolis, downtown St. Paul, Fort Snelling across the river,” he said. “You come to this place that’s right in the middle in the hub of the city and it washes over you that this is a really important place. We drive by all these sacred sites all day long. It’s right in the middle of the city and there’s airplanes buzzing overhead and semi trucks honking their horns, and that’s the thing about those places. They are sacred still for those people.”

St. Clair also talked about what she believes to be a long and ongoing erasure of the Dakota people from public attention, leading to lack of awareness for Dakota culture and sacred sites.

“In the public consciousness, I think Dakota people are often not considered,” she said. “Even in discussions and conversations of race, native people are not considered, and even in conversations of native people, Dakota people are often not considered.”

The long lasting impact of colonization on Native Americans is often overlooked, yet it is something that St. Clair believes makes it even more vital for non-Dakota people to be aware of the history of the land they live on.

While each landmark in the Mendota Heights area is significant in its own way, all are connected by sacred stories.

“All of these places have a connection to each other because they are associated with [bdote], the meeting of the rivers,” said McNally. “It’s like stories of Jerusalem for Christians or Jews, or Muslims with Mecca. Those places have a story and people carry those stories with them, so it’s not surprising that they have a deep connection to those places.”

Not only is bdote significant and meaningful for St. Clair as someone with Dakota heritage, but she also believes that it is important for non-Dakota people to recognize the history and meaning behind the places where they live and work.

“To have non-Dakota people understand the importance of these places, especially if these are places that they also visit or that are in their backyard or they enjoy, and to make that connection between this place and the Dakota people that have been here and are still here is a way to address that erasure. I think that’s important.”