The Armenia Genocide: a family memoir

Few Americans know of the tragic events, while political leaders are reluctant to speak the ‘g-word’

“Raise your hand if you have heard of the Holocaust.” Every single hand went into the air. “Now,” said former history teacher Elizabeth Van Pilsum in AP World History two years ago, “Raise your hand if you have heard of the Armenian Genocide.” I raised my hand and looked around. Twenty sets of hands remained motionless on their desks. Van Pilsum fixed her eyes on me and then on the class. She looked as if it was what she expected. I explained that the reason I knew about the genocide was that my Armenian great-grandmother was living in Turkey in 1915, the beginning of the violence. Growing up I knew the Armenian genocide was lesser noted than the Jewish Holocaust, but this moment put the lack of knowledge in perspective.

On September 30, 1915, the Saint Paul Pioneer Press stated, “Besought to intercede with his government and through it with the Turks in behalf of the Armenians, Ambassador von Bernstorff waved the whole matter aside by a sweeping assertion that the tales of Armenian massacres are pure moonshine.” Hidden in the chaos of World War One, much of the genocide went unnoticed and soon forgotten by many, but not all.

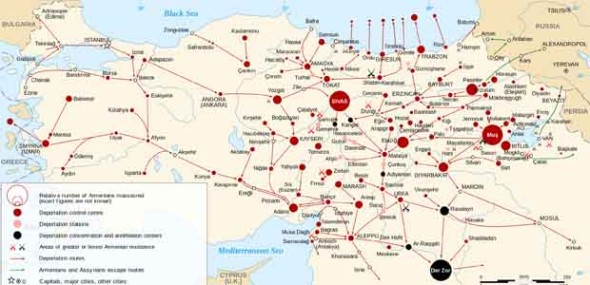

Beginning in 1915, the Ottoman’s government deported and executed as many Armenians as possible, starting with the men of the villages. Over the course of seven years, over 1.5 million Armenians were killed, which is over half the original population. Similarly to the Jewish Holocaust, the number of survivors was low.

One hundred years later, the Turkish government still refuses to acknowledge the atrocities of the Armenian Genocide. According to Taner Akcam in a paper he wrote while teaching at the U of M, in recent years the Turkish government has been attempting to convince its citizens that the UK is the one to blame for what is claimed to have happened during World War One. With slogans such as “UK should apologize to Turkey about Armenian genocide claims” and “Genocide [Claim Counter-]Attack” “England must apologize,” they attempt to erase history.

“It is important to understand the immorality and the harmful consequences of denying genocide. As prominent scholars of genocide such as Israel Charney, Robert J. Lifton, Deborah Lipstadt, Eric Markusen and Roger Smith have noted: the denial of genocide is the final stage of genocide; it seeks to demonize the victims and rehabilitate the perpetrators; and denying genocide paves the way the way for future genocides by making it clear that genocide demands no moral accountability or response,” said Peter Balakian in an Encyclopedia of Genocide 1. The denial of the genocide was present from the outset of the events. [Balakian spoke at the University of Minnesota on April 14, 2016, the day this issue of The Talon newspaper appeared.]

The muffled history of the Armenians led Adolf Hitler to believe the world would stand by as he exterminated the Jews. “Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?” He famously asked his advisors.

A great-grandmother’s story

My great-grandmother, Vartenie Dadian, was seven when the deportations began. Born in 1906 in the village of Yenije, Turkey, she grew up surrounded by family (six older siblings and three younger) and neighbors.

Syria

Israel

İzmir, Turkey

In 1910, the Turkish army began drafting Armenian men into their army and then executing them. Many Armenian men left the country for Europe and America to avoid being drafted. The remaining communities were left with mainly women, children and elderly. Among the men drafted was Vartenie’s father, Garabed. The family later heard news that he had been brutally tortured and hung.

Vartenie remembers her mother cleaning beans when the police entered her village and shouted that deportations would begin the next day. Her mother stayed awake all night cooking and preparing what little they could bring along. And just as announced, the entire village was marched away in the morning to a life of tragedy and uncertainty.

Vartenie’s family took their donkey, which the smaller children rode in the saddle bags while the adults walked alongside it. The families from Yenije banded together and sold what they had to buy food in hopes of survival. They were marched out of Turkey into Syria and traveled as far as Nazareth. After months of endless walking, only four members of the original 12 family members had survived and Vartenie’s mother, Shake, died in Nazareth.

Armenians from villages all throughout the country were driven away and forced to walk countless miles just as Vartenie’s had. Conditions varied between groups, but starvation, disease and execution were taking hundreds of thousands of lives as the Armenians were being marched away.

“There was no water, we were hungry, there was no food,” said Vartenie in an interview with Rose Akgulian in 1980 in Racine, Wisc. “Do you know those that went to Der Zor, they were all killed. The men from Tomarza which had earlier collected and taken away were killed. The ones that went to the army, few survived. But the ones who went in the Arabistan direction died of hunger. The Der Zor deportees were all killed. They had it very bad.”

After Shake died, the four remaining children were dispersed from each other for a few years. Vartenie was brought to Damascus by a relative where she lived in two orphanages run by the English government. During her stay, World War I came to a close in 1918, however, the persecution did not. After 14 months, her two remaining brothers and one sister gathered her and went to Adana, Turkey.

One of Vartenie’s brothers was shot in Adana. In 1921 the French army stationed there at the end of the war left, as did the Armenians. The three siblings fled to Izmir (then known as Smyrna), a Greek controlled city in western Turkey; by this time Vartenie was 12 or 13.

To make a living in Izmir, her brother rented part of a vineyard and many Armenians stayed together after all the atrocities they had experienced, but those atrocities were not finished. Just one year after their arriving, the Turks took control of the Greek port city. Upon the Turkish army’s arrival, they murdered and tortured Greeks and Armenians and set the Armenian sections of town ablaze. Desperately, the Armenians and Greeks flooded to the harbor in attempts to escape the violence. Vartenie was one of few who temporarily took refuge upon a barge and stayed there for seven days, forced to watch thousands of people burn to death and be killed by the Turks. Vartenie was finally able to escape with her sister on one of the last boats that eventually came to evacuate the survivors. Her brother was killed. The city was left in ashes.

An arranged marriage in Greece; arrival in America

After spending four years in an orphanage in Greece, Vartenie’s cousin, Hajy, who she had never met, in America arranged a marriage for her so she could come live here. It was customary for the father or older brother to pick a husband, but Hajy was now the closest relative for her. So in 1926, Mirhan Dadian, my great grandfather, arrived in Greece to marry Vartenie and then bring her to America.

Mirhan had left Tomarza in 1913 to avoid being enlisted into the Turkish army. He became an American citizen and served in the US military. Shortly after his arrival in Greece, they were married and set sail for Providence, Rhode Island. Upon landing, Vartenie decided to lie about her age to avoid suspicion since in reality she was only 18 and Mirhan was 33 years old. Soon after, they arrived to Racine, Wisc., which has a prominent Armenian community, similar to pockets of Los Angeles, Queens (New York) and Detroit. For three years, Vartenie and Mirhan struggled and lived in a one bedroom apartment with three other couples but eventually gathered enough funds to buy a house of their own. They raised four children, and Vartenie adjusted to the American life, becoming a citizen in 1940.

A survivor’s daughter learns through family stories of tragedy

“The culture, the religion, the activities and talk of the history was always part of our growing up,” said my grandmother, Shockey Julie, Vartenie’s youngest daughter. The tightly knit community carried a welcoming atmosphere and worked to ensure that their loss and history would not be forgotten by holding events and services to commemorate the genocide. Families bonded over their lost loved ones; there was not an individual left untouched by the events of the Genocide.

Unlike some survivors, including her father Mirhan, who avoided speaking of the tragedies of the genocide, Shockey remembers Vartenie often telling stories and reminding the community to never forget.

“My mother did [share stories of the genocide], and I’m always grateful for that,” she said.

Armenians in Minnesota

A century after the beginning of the genocide, the Armenian community continues to share their stories and commemorate those who were lost in the tragedies. St. Sahag Armenian Church in St. Paul is in preparation for the annual remembrance day, April 24. Father Tadeos Barseghyan leads Minnesota’s Armenian community and knows that every member has been affected by the genocide, whether a family member or friend, no one has been left the same.

“We had many events and programs last year to raise awareness about the Armenian Genocide because here in Minnesota not too many people know about it or have heard about it,” said Father Tadeos. Their efforts included holding events, running campaigns, posting on billboards and being covered in multiple newspapers. “People came [to the events] to learn about [the genocide] and to be with us and support us. They wanted to show that they want to learn about this,” said Father Tadeos. He received many letters and positive responses from those who attended the events.

Although 100 years have passed since the Armenians were starving in the Middle Eastern desert, the current day Syrian refugee crisis parallels a century’s old problem.

“It’s basically the same. If you look at the pictures, I mean it’s the same pictures, just back then they were black and white and today they are colorful pictures,” said Father Tadeos. The main difference he sees between them is that currently the reason for mass destruction is extreme radicalism, whereas in 1915 the motives were based more upon nationalism. Genocide has the same face and violence has no limitations, said Father Tadeos. Countless tragedies have taken place all over the world, and unfortunately many have gone down the same road and are forgotten.

Since AP World History class, I have never forgotten the surprise I felt when I realized none of my classmates knew about what my family experienced. Many events are forgotten in history, but then seem to resurface in modern day circumstances. As Vartenie said, “I’ll say, don’t forget my story of what we have been through.”

***